REVIEWS:

Erica Abeel:

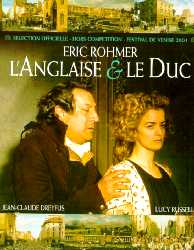

THE LADY AND THE DUKE

(Film Journal International)

INTERVIEWS:

L'ANGLAISE ET LE DUC

L'ANGLAISE ET LE DUC

Eric Rohmer. F 2001.

Produced by:

Pierre Cottrell (associate producer), Françoise Etchegaray (producer), Léonard Glowinski (executive producer), François Ivernel (executive producer), Romain Le Grand (executive producer), Pierre Rissient (associate producer)

Writing credits: Eric Rohmer

Source: Grace Elliott, Journal of My Life During the French Revolution

Cinematography: Diane Baratier

Camera Operator: Florent Bazin

Film Editing: Mary Stephen

Historical Advisor:Hervé Grandsart

Cast:

Jean-Claude Dreyfus (Le duc Philippe d'Orléans), Lucy Russell (Grace Elliott), Alain Libolt (Duc de Biron), Charlotte Véry (Pulcherie, la cuisinière), Rosette (I) (Fanchette), Léonard Cobiant (Champcenetz), François Marthouret (Général Charles Dumouriez), Caroline Morin (Nanon), Héléna Dubiel (Madame Meyler), Laurent Le Doyen (Officier section Miromesnil), Georges Benoît (Miromesnil section head), Serge Wolfsperger (Adjoint section Miromesnil), Daniel Tarrare (Justin, le portier), Marie Rivière (Madame Laurent), Michel Demierre (Chabot), Serge Renko (Vergniaud), Christian Ameri (Guadet), Eric Viellard (Osselin), François-Marie Banier (Robespierre), Henry Ambert (Employé mairie Meudon), Charles Borg (Officier 1 barrière de Vaugirard), Claude Koener (Officier 2 barrière de Vaugirard), Jean-Paul Rouvray (Officier 3 barrière de Vaugirard), Axel Colombel (Badaud 1 Couvent des Carmes), Gérard Martin (IV) (Onlooker at Carmelite convent), Gérard Baume (Man on Boulevard Saint Martin), Joël Templeur (Officier patrouilleur Versailles), Bruno Flender (Soldat 1 corps de garde), Thierry Bois (Soldat 2 corps de garde), William Darlin (Ivrogne corps de garde), Anne-Marie Jabraud (Madame de Gramont), Isabelle Auroy (Madame de Châtelet), Jean-Louis Valéro (Chanteur), Michel Dupuy (Portier rue de Lancry), Pascal Ribier (Soldat), Emma Le Doyen, Anthony Dunand, Elisabeth Morat, Marc Ligaudan, Maria Da Silveira, Luc-Antoine Salmont, Alain Uguen, François Rauscher, Edwige Shaki, Antoine Beau, Jerome, Beaudet, Jacques Meunier, Pierre Sambet, Lucette Labreuil, Duy D'Argences, Martine Hatrisse

Production Design: Antoine Fontaine

Production Management:

Antoine Beau (production manager), Jean-Pierre Giudice (unit manager), Karim Moundy (unit manager), Antoine Moussault (unit manager), Jean-Francois Vendroux (unit manager)

Set Decoration: Lucien Eymard

Costume Design: Nathalie Chesnais, Pierre-Jean Larroque

Makeup Department:

Véronique Hebet (hair stylist), Marie Luiset (makeup artist), Jacques Maistre (key makeup artist), Annie Marandin (key makeup artist)

Art Department:

Lucien Eymard (property master), Jean-Baptiste Marot (paintings), Jérôme Pouvaret (chief constructor)

Sound Department:

Jonathan Liebling (sound effects editor), Pascal Ribier (sound)

Visual Effects:

Patricia Boulogne (visual effects), Buf Compagnie (visual effects), Olivier Dumont (visual effects), Stéphanie Fribourg (visual effects), Francesco Grisi (visual effects), Anne Gros Lafaige (visual effects), Wilfried Jeanblanc (visual effects), Jonathan Lagache (visual effects), Jean-Philippe Leclercq (visual effects), Halim Negadi (visual effects), Hervé Thouement (visual effects)

Plot:

France 1790. Scots divorcee Grace Elliott (Lucy Russell), 30, former mistress of the Prince of Wales, has settled in Paris, brought over by Prince Philippe, Duke of Orléans (Jean-Claude Dreyfus). Orléans, cousin to Louis XVI, is supported by the revolutionary Orleanist faction as successor to the throne. Grace is no longer his mistress, but a close friendship continues, despite their disagreement about the Revolution (owing to her passionate royalism and his radical sympathies).

On 10 August 1792 the Tuileries Palace is stormed; Louis XVI is imprisoned and his Swiss Guards massacred. Grace Elliott escapes to her house at Meudon. On 3 September, in the midst of the September massacres, she bravely returns to Paris to help an unnamed fugitive. It is not Orléans but the wounded Marquis de Champcenetz (Leonard Cobiant), governor of the Tuileries, and a personal enemy of Orléans. Despite great danger, she shelters him, and for her sake Orléans aids Champcenetz to escape to England. In January 1793, despite his vows to stay away or abstain, the Duke votes for the King's execution at the Revolutionary Council. Six weeks later, ill with grief and persecuted by searches, Grace decides to visit the Duke to ask his help in obtaining a passport. Powerless, he soon warns her to destroy all documents. A fresh search finds a letter in English; she is arrested and taken to Robespierre's (Francois-Marie Barier) Comité de Surveillance, where she sees Orléans, himself under suspicion. She is released by Robespierre when the letter is translated. But the Duke is arrested, and executed on 5 November. Grace is rearrested, but Robespierre's fall saves her life and she returns to England.

(Source: Sight & Sound, February 2002)

Reviews:

Erica Abeel:

THE LADY AND THE DUKE

With his new film, 81-year-old Eric Rohmer goes digital to mount a historical drama about the fortunes of Lady Grace Elliott (Lucy Russell), a Scottish expatriate living in Paris during the French Revolution. The Lady and the Duke is short on the romantic voltage typical of Rohmer, and despite the period's tumult, the plot, which dwells on Grace's personal notions of honor, remains perversely static. And though it's certainly original to revisit the Revolution from an aristocrat’s perspective, Rohmer's pro-monarchy bias may raise hackles. Still, the film fascinates through its visual beauty and sheer oddness, like some curious objet d’art impossible to classify.

Adapting from the real Grace Elliott's memoir, Rohmer follows the evolution of her friendship with her former lover, the Duke of Orleans (Jean-Claude Dreyfus). Indifferent to his warnings and loyal to the crown, she remains in Paris to brave the Terror—even after watching a pack of sansculottes brandishing the head of a princess friend on a pike. In a tense scene, she hides a fugitive nobleman, literally between her mattresses, from a bloodthirsty citizens' 'patrol'—for the principle of the thing, though he's a man she despises. After failing to persuade the Duke to vote against the King's death, she bitterly witnesses the execution at a distance, from the terrace of her house in Meudon. Reconciliation with the Duke arrives only on the eve of his own beheading, a fate Grace escapes through her ties to liberals sympathetic to the Revolution.

By design, the film courts artifice rather than attempting a realistic copy of 18th-century Paris. Rohmer shot before a blue screen and superimposed the cast onto tableaux specially painted by Jean-Baptiste Marot, based on the layout of the city at that time. The effect is rather like paintings from the Musee Carnavalet suddenly sprung to life. Add the mannered, super-enunciated French spoken by the principal characters, and you get a strange hybrid, part theatre, part cinema, part tableau vivant, recombined through digital technology. Lucy Russell, a patrician blonde straight from a Gainsborough portrait, conveys the female forcefulness of character often celebrated by Rohmer. Suspense reigns in the cat-and-mouse games the nobles were forced to play with the revolutionaries to elude the guillotine. Above all, let's salute Rohmer's ability at 81 to bend the latest technology to his unique cinematic vision. Given Hollywood's fetish for the flavor du jour, how refreshing to watch a filmmaker who refuses to bow to fashion.

(Source: FilmJournal International, 2002-06-05.)

Interviews:

Interview with Eric Rohmer |

|

Aurélien Ferenzi: How did the idea of The Lady and the Duke come to you?

Eric Rohmer: While on holiday about ten years ago, I came across a digest of the memoirs of Grace Elliott in a history magazine. This English lady had been the mistress of the Duke of Orleans, King Louis XVI's cousin, and had written an account of her life during the French Revolution. The article mentioned that her town house was still standing at such-and-such a number on Rue Miromesnil. I have always been interested in places and was particularly struck by the idea that this house could still be seen at a certain address. That gave me the idea of making a film that would be set in that particular spot in Paris and would play on the relationship between the peaceful apartment, which served Grace as a kind of hideout, and the rest of the city in the throes of revolutionary turmoil. Strangely enough, I found out later that the article in the history magazine was wrong: the house on Rue Miromesnil had been built after the Revolution, so Grace Elliott couldn't have lived there! But without that mistake, I'm not sure the article would have sparked off the idea in me.

Aurélien Ferenzi: The portrayal of Paris was the driving force behind the film …

Eric Rohmer: Yes, and I had to find a way of depicting historical Paris. I'm often frustrated when I watch period pieces set in Paris. People always tend to go off and film in Le Mans, Uzès or other towns with well-preserved historic neighbourhoods. I can always tell it's not Paris, which has its own specific architecture. I didn't want that, nor did I want to make do with filming the same handful of old carriage doorways that always feature in period films. I wanted to show a big city with big open spaces like Place Louis XIV (now Place de la Concorde), which was a focal point of the Revolution, and the parts of town that Grace Elliott mentions in her memoir: Boulevard Saint-Martin, Rue Saint-Honoré, down which she is taken on her way to the Surveillance Committee, and so on. When she says she walked all the way to Meudon via the Invalides, she had to cross the Seine somewhere!

Aurélien Ferenzi: So what was the solution you came up with?

Eric Rohmer: I had shot two period films before: The Marquise of O (1975) in real locations and Perceval le Gallois (1978) entirely in the studio. I knew that neither of these methods would give an authentic portrayal of Paris. So I had the idea of inserting real-life characters into scenic backgrounds that I would have specially painted, based on the layout of the city at that time. Inserting characters into sets is one of the oldest tricks in the filmmaker's book. Méliès was probably the first to do it. But ten years ago, when I first started thinking about the project, digital technology was still in its infancy. If the characters and scenery had been composited on film, each new layer would have incurred a loss of picture quality. Kinescoping, i.e. transferring from video to 35mm film, wasn't very satisfactory either in those days. Now both of these techniques have been perfected.

Aurélien Ferenzi: How did you have the scenic backgrounds made?

Eric Rohmer: They were painted by Jean-Baptiste Marot. We designed them together in the appropriate period style and according to the requirements of the mise en scène. Hervé Grandsart did the preliminary documentary research. We worked from pictures and engravings, but also from street maps of the period. The interiors are not real locations. They were all built in an adjoining studio by the set designer, Antoine Fontaine, and the rigger, Jérôme Pouvaret. To me, this work was not just a matter of being meticulous it was about striving for an authenticity that underpins the whole film. At heart, I wasn't especially intent on making a film about the Revolution. I don't much like being pegged as an 18th century buff! Even though I've sometimes been compared to Marivaux, it isn't my favourite century.

Aurélien Ferenzi: Was your approach comparable to the way you made Perceval: using pictures from the period to depict the period itself?

Eric Rohmer: Yes. I don't much care for photographic reality. In this film, I depict the Revolution as people would have seen it at the time. And I try to make the characters more like the reality you find in paintings. The opening scenes of the film are pictures, and I'd be pleased if the uninformed spectator thought they were period paintings and was surprised when they suddenly come to life.

Aurélien Ferenzi: One is also reminded of your work in educational television.

Eric Rohmer: I didn't make this film for any political reasons. I don't use it to defend any party, royalist or anti-royalist. On the other hand, I would like to help cultivate a taste for history in audiences, both old and young. I have heard it said that France is the country that publishes the largest number of history magazines, whereas the English-speaking world has more taste for historical novels. There is a huge potential interest in history in France, but period films have often been rather lax about historical exactitude. In fact, my scrupulousness is the reason why I have only made three period films. I pay close attention to the language of a period and it's very difficult to write dialogue in the words of a different era. It keeps the characters from expressing themselves. If I used my own style to write a story in the past, it would be a pastiche. It wouldn't be any good. Here, Grace Elliott's story gave me a very sound basis, right down to the dialogue.

Aurélien Ferenzi: Did you watch other historical films again before starting on The Lady and the Duke?

Eric Rohmer: I watched three period pictures: D.W. Griffith's ORPHANS OF THE STORM (1921) (which is set during the French Revolution), Abel Gance's NAPOLÉON (1927) and Jean Renoir's ![]() LA MARSEILLAISE (1937). All three films are admirable for different reasons. For example, for a long time Renoir was praised for making his characters speak as they did in the 1930s and not bothering about 18th-century speech. That's a myth, unless we believe that the language of the 1930s was closer to the 18th century than our own! Griffith made me realize something else: I was wondering how to film the exteriors, i.e. how to insert the characters into the scenery. Would I film sequence shots or reverse angle shots, which would make the process even more complicated to set up? Seeing Orphans of the Storm again, I realized that most of the time, its strength is that each shot is static. So I took static shots, and closer shots with a second camera.

LA MARSEILLAISE (1937). All three films are admirable for different reasons. For example, for a long time Renoir was praised for making his characters speak as they did in the 1930s and not bothering about 18th-century speech. That's a myth, unless we believe that the language of the 1930s was closer to the 18th century than our own! Griffith made me realize something else: I was wondering how to film the exteriors, i.e. how to insert the characters into the scenery. Would I film sequence shots or reverse angle shots, which would make the process even more complicated to set up? Seeing Orphans of the Storm again, I realized that most of the time, its strength is that each shot is static. So I took static shots, and closer shots with a second camera.

Aurélien Ferenzi: Were you always sure that the characters could be keyed in as you wanted?

Eric Rohmer: We ran tests. We had to know how the characters would fit into the scenery, so we filmed a test with extras going through a doorway and it worked. We sometimes had to adapt a little, especially when the set was deeper than the length of the studio. For instance, the view down Rue Saint-Honoré had to be 200 metres long, while the sound stage was only 40 metres wide. We had to shoot that sequence in several parts with cutaway shots in between. It was a constraint, of course. I normally decide how to shoot each scene as I come to it, whereas here I had to design the shots very precisely beforehand. But the advantage is that the result is truer than if I had edited it all together from little bits of houses and roofs framed from odd angles to cut out the TV aerials. That wouldn't have interested me. I like to show the scenery as it is. On the set, I often hear people say "We'll cheat it." I don't like cheating. I like to take reality the way it is, even if it's a reality I created through painting, like here. Truth comes from the painting, not the editing. You could say I'm faithful to Bazin's teachings, even if he was too hidebound regarding depth of field and the sequence shot. And I do think that resorting to a highly visible artifice gives me truth.

Aurélien Ferenzi: To return to the story itself, what appealed to you in Grace Elliott's memoirs?

Eric Rohmer: My researcher found me a complete copy of the text, which had been published several times in France. Grace Elliott was born in 1760 and died in 1823. Her journal begins on 14th July 1789 and ends just before she was let out of prison, after the fall of Robespierre. Over and above its undeniable historical interest (it contains a few minor errors in dates, but most of it has the ring of truth), there is something striking about it, as though it had already been written as a script, with scenes, sequences and even dialogue. It has a very different tone from the other journals I have read. Memoir-writers mostly tend to write about themselves, their fears and hopes, but Grace Elliott includes herself in the picture, though always maintaining a certain detachment and distance. We see her acting and moving around, but the other characters also live in a very powerful way, especially the Duke of Orleans, of whom we have very few first-hand reports.

Aurélien Ferenzi: Was it her loyalty to her commitments that touched you?

Eric Rohmer: No, it was more her British stiff upper lip: a certain modesty and self-control, a completely unaffected way of talking about herself and, above all, a way of looking at events that makes her the heroine of a novel. Perhaps this is how it happens when History overturns the lives of individuals. Few other historical characters have ever seemed so close to us, and so moving. I can only talk about my intentions, not about the result, but the details of her private life that appear in the book, which I kept in the film, create an effect of reality. For example, I'm thinking about the moment when Orleans looks at his watch. We're in the present, in the moment. That's what makes it filmic. The past is the tense of the novel; the present is the tense of cinema.

Aurélien Ferenzi: You were also interested in the light the characters shed on the events of the Revolution.

Eric Rohmer: What interests me is their lack of fanaticism. Grace stands up for the King but she is not an extremist. She doesn't want to leave France. She has Republican friends such as Orleans and Biron. She is probably actually less of a royalist than she says, given that she wrote her book in anti-Revolutionary England. As for Orleans, he is often shown in a totally negative light, but there is a mystery, an ambiguity, a duality about him that interests me. He was vindictive and he didn't like Louis XVI, but he was also sincerely attracted to new ideas. I have added some details drawn from his own correspondence and the testimony of his son, Louis-Philippe.

Aurélien Ferenzi: The audience might be inclined to condemn the killing of the King, as Grace does.

Eric Rohmer: I think that at the time, everyone wanted the King dead for fear of appearing reactionary. It was the trend then, rather as it is the trend nowadays to claim to be an environmentalist. I wanted to make my film with Grace Elliott's story, not against it. If anyone wants to pass judgment on historical grounds, they should judge the book on which the film was based, not the film itself.

Aurélien Ferenzi: How did you choose the actors?

Eric Rohmer: By intuition, as always. I audition one person, he or she reads the lines, and that's it! I had difficulty casting the Englishwoman. A casting director known to Margaret Menegoz sent me photos of actresses and an audio tape of their voices. The only tape I liked was of an actress who said she knew Grace Elliott's book and wanted to play her. Her voice appealed to me before her photo did, and when I met her, I found the actress even more attractive than her picture! As for Jean-Claude Dreyfus, I didn't think of him at first, but I was looking for a strong personality. I needed somebody big and stout, even if he didn't physically resemble the Duke of Orleans all that closely. I am very pleased with the cast. My directing of actors, as usual, went no further than giving them technical instructions. Feelings are the actor's business. All I did was tell them to enunciate clearly so that they would be understood. They didn't let me down.

Aurélien Ferenzi: Do you think the film will surprise audiences used to your Comedies and Proverbs and Tales of Four Seasons?

Eric Rohmer: No, and besides, whenever I have made slightly different films, be they historical or political, like The Tree, the Mayor and the Media Centre (1992), the audience has followed. I wouldn't want to limit myself to overly psychological topics or romantic comedies, even if that's where I feel most personally involved. I like to get out from time to time.

(Source: Senses of Cinema - © Aurélien Ferenzi, 2001)

Interview with Eric Rohmer

by Thilo Wydra

Eric Rohmer: Bonjour. Deutsch kann ich mit Ihnen wohl nicht sprechen, obwohl, ich war ja mal in Deutschland, aber seitdem (auf deutsch) 'ich habe es vergessen'. Ich bin es nicht mehr gewohnt, und die Wörter wollen nicht mehr kommen...

Frage: Sie sprechen von den Dreharbeiten zur "Marquise von O"?

Rohmer: Ja, das war 1975. Und ich machte dort auch Urlaub, in den Bergen, und erlernte die Techniken des Alpinismus (lacht). Aber auch das habe ich verlernt.

Frage: Gut 25 Jahre nach der Kleist-Verfilmung nun wieder ein historisches Sujet...

Rohmer: ...wobei das ja alles Legende ist: historisches Sujet, historisches Personal, historisch...doch sind es auch hier Menschen, die Mätresse Grace Elliott und der Herzog von Orléans, die eine private Geschichte haben, und er wird schließlich guillotiniert. Wir befinden uns also mitten in der Historie, aber sie spielt sich in einem privaten Boudoir ab. Das war es auch, was mich interessierte: Alles spielt sich innen ab, und sobald die Personen mal das Haus verlassen, geschehen schreckliche Dinge. Und: Es ist die Sicht auf die Geschichte, aber in Kulissen. Es wird nichts gezeigt. Alles spielt sich hinter dem Vorhang ab. Das hat mich interessiert, dieses Versteckte, dieses Nicht-Sichtbare.

Frage: Haben Sie aus diesem Grund alles konstruieren und malen lassen? Damit sich alles auf das private, das intime Moment konzentriert?

Rohmer: Ja, auf alle Fälle, ich wollte einfach ganz wenig Außen zeigen, und ich wollte, dass die Bilder stark sind, dass sie charakteristisch sind. Auch, dass man Paris sofort wieder erkennt. Ich wollte nicht in die Provinz oder gar in die Tschechei fahren und dort alte Häuser aufnehmen, wie sie damals vielleicht waren. Paris hat sich verändert, also habe ich einfach alles malen lassen. Ich wollte ein 'wirkliches' Paris. Kein nachgebautes, so wie es die Amerikaner machen, was ich im Übrigen sehr angreifbar finde.

Frage: Sie haben nun erstmals auf Video gedreht.

Rohmer: Es war so alles viel einfacher. Und ich wollte auch nicht mit verschiedenen Materialien arbeiten. Also wurden die Videoaufnahmen später umkopiert auf 35-mm-Scope-Film, den es wiederum schon ewig gibt.

Frage: Ist Ihre historische Geschichte modern? Das Aktuelle im Alten?

Rohmer: Nun gut, das lässt sich auf vieles anwenden. Was mich eher interessiert, ist der Sinn einer Geschichte, der Geschmack einer Geschichte. Innerhalb der Historie gibt es immer Bezüge und Referenzen. Wobei ich es schade finde, dass sie in Frankreich etwas vernachlässigt wird. Die Kinder heute, sie wissen deutlich weniger als das noch bei uns der Fall war. Ist das auch in Deutschland so?

Frage: Der Umgang der Deutschen mit der Geschichte...

Rohmer: ...oder mit dem Kino, mit der Sprache...

Frage: ...es verändert sich eben alles sehr schnell. Die deutschen Autorenfilmer etwa sind dem jungen Publikum kein Begriff mehr.

Rohmer: Drehen die denn noch? - Mich stört auch der Umgang der französischen Intellektuellen mit der Sprache. Das schockiert mich. Diese Amerikanismen. All das.

Frage: Filmgeschichte ist aber auch, dass Sie zusammen mit Claude Chabrol 1957 ein Buch über Alfred Hitchcock schrieben, das ihn in Europa erst salonfähig machte.

Rohmer: Ja, und er hat danach wunderschöne Filme gemacht, und wir haben es nicht mehr gewagt, weiter in Buchform darüber zu schreiben.

Frage: Können Sie sich noch an ihren ersten Hitchcock erinnern?

Rohmer: Der allererste? Oh! Da bin ich mir unsicher. Ob es vielleicht "Shadow of a Doubt" war? Oder "Notorious"? Oder doch "Rope"? Ich habe damals einige zur gleichen Zeit gesehen, auch "Spellbound" und "Rebecca", den ich wirklich sehr mag. Eigentlich die Filme der 40er und 50er Jahre. Und das Buch erschien nach "The Wrong Man", und was mich ärgerte war, dass wir "Vertigo" nicht mehr dabei hatten, der in jenem Jahr entstand, leider - für mich stellen die Filme mit James Stewart eine Art Trilogie dar, mit "Rear Window" und "The Man Who Knew too Much". Und natürlich hat er auch später sehr wichtige Filme gedreht, allein "Psycho" und "The Birds", selbst "Marnie" finde ich gut.

Frage: ...bis hin zu "Frenzy" und zuletzt "Family Plot".

Rohmer: Ja, "Frenzy"! Ein sehr schöner Film!

Frage: Hat Hitchcock jemals oder gar bis heute Einfluss auf Ihre Arbeit gehabt?

Rohmer: Nehmen Sie meinen Freund Chabrol und mich: Bei Chabrol taucht Hitchcock in den Sujets auf, er liebt diese kriminellen Verstrickungen. Bei mir hingegen taucht nichts davon in meinen Sujets auf. Aber ich glaube, dass es bei mir in der Art und Weise, eine Geschichte zu erzählen, auftaucht. Auch sein Suspense ist etwas, was mich nach wie vor sehr interessiert. Ich mag das auch, den Zuschauer quasi zu befragen, was wird wohl als nächstes geschehen? Und ich mag dieses Psychologische bei Hitchcock. Übrigens - ich habe auch einen deutschen Cinéasten bewundert, Murnau. Auch Fritz Lang. Und für Amerika natürlich Hawks. Jean Renoir wäre hier noch zu nennen, ein großer Cinéast dieser Nation. Es gibt noch Rossellini...man hat immer mehrere Vorbilder, Einflüsse, auch ich habe mehrere Meister, nicht nur einen. Auch wenn ich über Hitchcock dieses Buch geschrieben habe.

Frage: Ein sehr wichtiges, das den Blick auf ihn völlig veränderte. Er war nicht länger nur der Master of Suspense, der Thriller-Regisseur.

Rohmer: Sicher, sicher, längst gehört er zu den Ernstzunehmenden. Heute ist das in der ganzen Welt so. Aber damals, zu Beginn, waren wir die einzigen, wir standen allein mit dieser Haltung. Und André Bazin, der nicht wirklich ein purer 'hitchcockien' war, ihn nannte ich einen 'hitchcocko-hawksien' (lacht). Und der Einfluss Hitchcocks auf uns alle, jeder hat ihn anders interpretiert, und unsere Filme ähneln sich wirklich nicht, seit langer Zeit nicht mehr. Ich ähnelt weder Rivette, noch Godard, noch Chabrol, noch Truffaut - jeder hat seine eigene Stimme, jeder hat seinen Weg gemacht. Diese Einflüsse, man muss sie vergessen.

Frage: Sprechen wir wieder über heute - haben Sie nun, nach L'ANGLAISE ET LE DUC, neue Projekte?

Rohmer: Eigentlich spreche ich nie über Projekte, aber ich habe welche, wobei ich nicht weiß, welches es nun werden wird. Für dieses Jahr habe ich keines, ich arbeite nun langsamer. In den 80er Jahren habe ich ja fast jährlich einen Film gedreht. Das ist vorbei. Es wird langsamer...

Das Gespräch führte Thilo Wydra

(Source: www.br-online.de)